The Anatomy of Twigs: Growth, Transport, and Identification

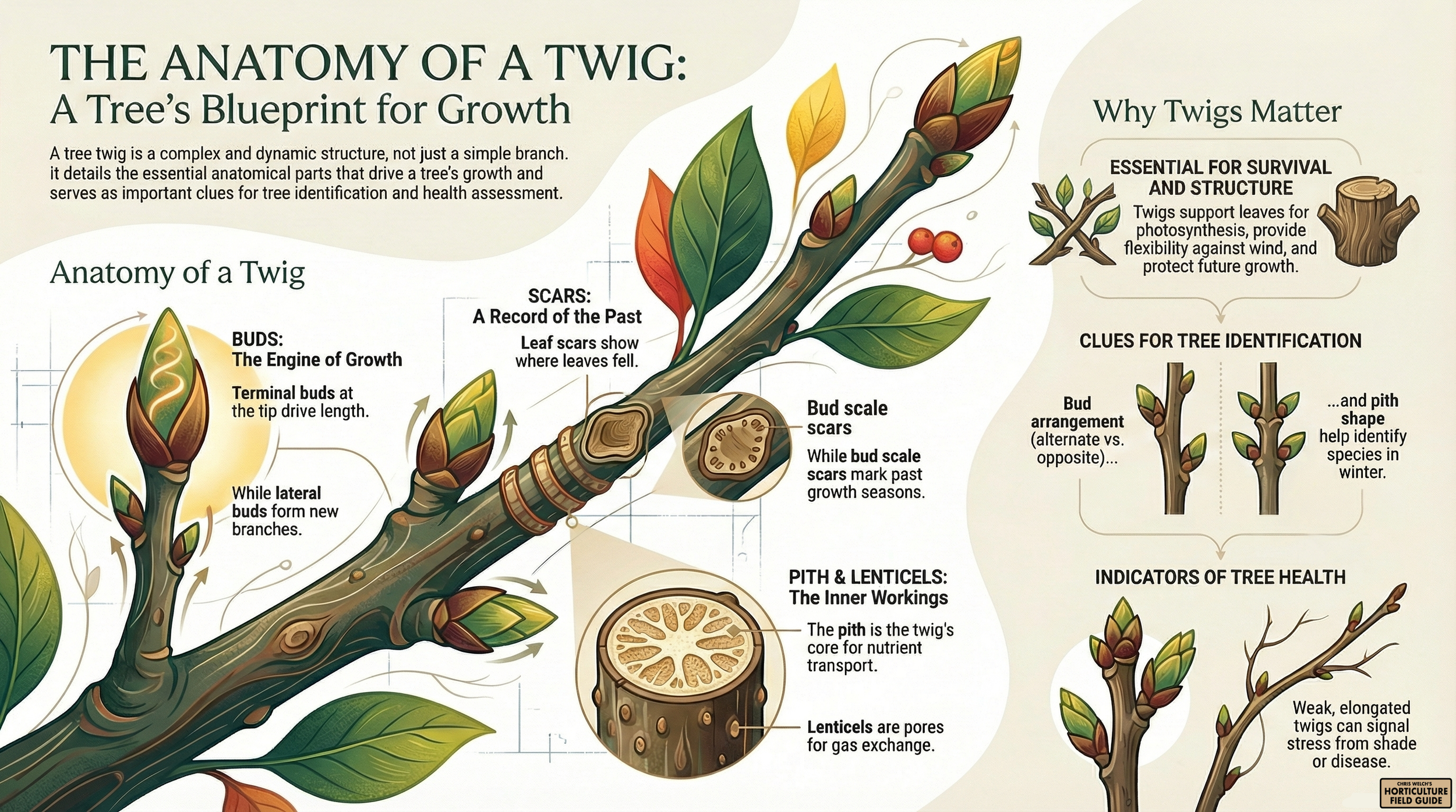

Twigs, the small, slender extensions of a tree’s branch system, might seem insignificant, but they are the vital growth engines of a tree. They host leaves and flowers, fueling the essential processes of photosynthesis and reproduction.

These unassuming appendages are miniature lifelines, efficiently transporting water and nutrients through internal tissues such as the pith and xylem. Critically, twigs house the buds of next season’s growth, allowing trees to reach for sunlight, create flexible structural forms, and adapt to environmental stress. In short, understanding the anatomy of the twig is key to understanding the tree’s survival strategy.

Arborists spend significant time studying woody twigs. Features like bud patterns, leaf scars, and pith shape are crucial for tree species identification and quickly assessing a tree’s health and vitality. By observing how a twig grows toward light (a process called phototropism) and how it adds strength to branches (reaction wood), we gain insight into the mechanisms that are crucial for long-term tree stability and form.

Key External Features for Twig Identification

To truly understand how a twig functions, we must identify its core components:

Apical Meristem: This is the region of actively dividing cells located within the terminal bud at the tip of the twig. It is the primary point of vertical growth for the stem and branches, driving the tree’s upward and outward expansion.

Terminal Bud: The bud located at the very tip of a twig, responsible for future length growth. Once it opens, the terminal bud scar (a ring of marks left where the bud scales fell off) can be used to estimate a twig’s age and past annual growth rate.

Lateral Buds: These are smaller buds found along the sides of the twig, typically nestled just above a leaf scar. These generally remain dormant (inactive) but can grow into new branches if the apical meristem is damaged or released from dormancy by shifting plant hormones.

Lenticels: Small, raised pores found in the bark of twigs and young branches. Lenticels are vital for tree respiration, allowing gases such as oxygen and carbon dioxide to exchange between the internal tissues and the atmosphere.

Inside the Twig: The Transport and Support Systems

While the exterior features, like buds and lenticels, tell a story of growth, the true engine of the twig lies within its cross-section. These internal tissues are responsible for critical functions such as structural support, water conduction, and nutrient storage.

Internal Structures:

Pith: Located at the center of the twig, the pith is made up of soft, spongy tissue that functions primarily in the storage of nutrients and water. Pith cells are usually large and thin-walled. The shape of the pith (solid, hollow, chambered, or diaphragmed) is a highly reliable indicator of the dormant state of trees and shrubs.

Xylem (Wood): The primary component of the woody part of the twig. The xylem’s primary role is the upward transport of water and dissolved minerals from the roots to the leaves. The xylem cells are thick-walled and provide the necessary structural support that allows the tree to stand tall and resist bending forces.

Vascular Cambium: A thin, lateral layer of cells situated between the xylem (wood) and the phloem (inner bark). This is a meristematic tissue responsible for the secondary growth of the twig, producing new xylem toward the inside and new phloem toward the outside, increasing the twig’s diameter.

Phloem (Inner Bark): Located just outside the vascular cambium, the phloem’s primary function is the downward transport of sugars (food) produced during photosynthesis from the leaves to the rest of the tree (roots, buds, and fruit).

Bark (Cortex and Epidermis): The outermost protective layer of the twig. The outer layer (epidermis) protects against water loss and pathogens, while the inner layer (cortex) may also store starch and other substances.

By examining the cross-section, an arborist can gauge the health of these layers; a healthy, active cambium, for instance, is a sign of robust growth.

Twigs as Nature’s ID Cards: Identifying Trees in Winter

While leaves offer the most obvious clues for tree identification during the growing season, twigs become the most reliable feature once the leaves have fallen. Arborists use a few key twig characteristics to distinguish species with certainty, even in the middle of winter.

Essential Identifying Features

Bud Arrangement: This is perhaps the most reliable characteristic. Buds are positioned on the twig in one of three primary ways:

Alternate: Buds are staggered, appearing alone at each node (e.g., Oaks, Maples).

Opposite: Buds are positioned directly across from each other at the same node (e.g., Ash, Dogwood).

Whorled: Three or more buds are clustered at a single node (rare, but seen in some plants).

Pith Shape and Condition: The central pith can be checked by slicing a twig lengthwise. Its shape is a definitive identifier:

Solid: Uniformly filled with tissue (e.g., Birch, Willow).

Chambered: Divided into hollow sections by thin, horizontal plates (e.g., Walnut, Persimmon).

Diaphragmed: Solid but with thicker, firmer partitions (e.g., Magnolia).

Leaf Scars and Vascular Bundle Scars: When a leaf falls off, it leaves behind a leaf scar on the twig. Within this scar are tiny, dot-like marks called vascular bundle scars, which indicate where the veins entered the leaf. The shape of the leaf scar and the number of bundle scars are unique to many species.

Color and Texture: Subtle characteristics, such as the twig’s color and surface texture (hairy, smooth, or glossy), provide secondary but helpful clues.

By observing these features, the arrangement of the buds, the condition of the pith, and the scars left by last year’s leaves, anyone can learn to read a twig and unlock the identity and life story of the tree it belongs to.

Conclusion

A twig is much more than just a connector. It’s a key part of a tree’s growth, strength, and history. Its tips help the tree grow taller, and its inner parts move water and nutrients. Every part of the twig, inside and out, is vital for the tree’s survival. By learning to recognize twig features, anyone can better understand how trees live and thrive.

Additional Reading and Resources

For those interested in delving deeper into the botanical structures and practical skills discussed here, these resources provide excellent, detailed information:

Coder, Kim D.

Warnell School of Forestry and Natural Resources, University of Georgia.

https://warnell.uga.edu/sites/default/files/inline-files/Tree%20Anatomy%20Twigs%20pub%2012-24%20-%20Tree%20Anatomy%20Manual%20Twigs%20ARBOR-H.pdf

Clarendon College.

Botany Lecture Outline: Stems and Twigs.

Department of Natural Sciences.

http://programs.clarendoncollege.edu/programs/natsci/biology/botany/online%20lecture%20outlines/stems.htm